Louise Bennett-Coverley, “Miss Lou,” died at her Toronto home on July 26, 2005 and was honoured with an official funeral in Kingston, on August 9 at National Heroes Park. Writer, actress, poet, singer, folklorist, comedienne, queen of culture, and Soul of Jamaica, she lived in Canada for the last decade of her life, and built up a wide following of Jamaican nationals in Toronto and across Canada.

Born in Jamaica on September 7, 1919, Miss Lou was an international figure. Her obituaries appeared in several of the world’s major media including the Toronto Star, the Globe and Mail, the London Times, The Chicago Tribune, the Los Angeles Times, the Guardian, the Sun Sentinel, the Scotsman, the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Dallas Morning News, the BBC, the CBC, the Victoria Times Colonist, the Gleaner, the Jamaica Observer and the New York Times.

Miss Lou’s father owned a bakery in Spanish Town but died when she was only seven. Her mother, an accomplished dressmaker, instilled respect (“everybody was a lady — the fish lady, the yam lady, the store lady, the teacher lady”), and nurtured her, unknowingly setting the stage for the most influential figure in Jamaican culture.

She was a model professional on stage, radio, and television. In her many roles she demonstrated that Jamaican Creole could be the medium of significant art. She began performing at church concerts, around campfires and for her school friends at an early age. But she knew she wanted to write.

Her early attempts were in Standard English. Then, one day, as a well-dressed teenager boarding a tramcar, she heard a market woman at the back say to another, “’Pread out yuself, one dress-ooman a come!” The remark grabbed her attention and became the basis of her first dialect poem, Spread out yuself Liza.

She began to wonder why more Jamaican writers were not writing about local realities and in the language many people spoke, instead of writing in the same old English way about Autumn and things like that. Later in her career, she would write in defence of Jamaica talk. In her poem Bans a Killin, the persona enquires with wicked wit:

Meck me get it straight, Mass Charlie,

For me no quite understan —

Yuh gwine kill all English dialec

Or jus Jamaica one?

Dah language weh yuh prou o’

Wha yuh honour and respeck

Po’ Mass Charlie: Yuh noh know sey

Dat it spring from dialect!

Louise Bennett was a teenager when she first appeared at a 1936 Christmas Day concert at Coke Hall, reciting a poem in dialect.

She received a prize of two guineas from impresario Eric Coverley and bought a pair of shoes with the money.

Following in the footsteps of Jamaican poets Claude McKay and Inez Knibb Sibley (great grand-daughter of Baptist missionary William Knibb who authored a number of books including one in dialect called Quashie’s Reflections), she continued to write in dialect. Not surprisingly, she was ostracised by the educated in what was yet colonial Jamaica.

But the people loved her and brightened up whenever they heard their language in her skits, her songs or her poetry. She saluted this love in return by fashioning her costume after that of the traditional Jamaican market woman. The fabric, she explained, was not African but originated in India – as did many residents of Jamaica.

She performed in her first Christmas pantomime in 1943, and she and Ranny Williams quickly became the leading duo of Jamaican theatre. They wrote many pantomimes, in the process converting the pale imitation of English pantomime into the vibrant Jamaica Pantomime. They also created the popular Lou and Ranny Show for JBC radio.

Her most influential recording is probably her 1954 rendition of the Jamaican traditional song Day Dah Light, which was recorded by Harry Belafonte as Day O, also known as The Banana Boat Song. Belafonte’s famous version was one of the 1950s’ biggest hit records, leading to the very first gold record ever awarded.

In 1945, she won a British Council scholarship to the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London and was the first Black student there. She then hosted a BBC radio show, Caribbean Carnival, and worked with repertory companies and revues all over England. On her return to Jamaica two years later she taught drama to youth and adult groups in social welfare agencies and for the Extra-Mural Department of the University College of the West Indies.

More to the point, she threw herself fully into her work with Jamaica Welfare as a devotee to and emissary of the National Movement, working through organisations like the Jamaica Federation of Women, the Jamaica Agricultural Society, and the 4-H Clubs to help create the new Jamaica.

This took her to schoolrooms all over Jamaica at night, teaching the people through poetry and song about their mores, who they were and how they should aspire to live. Her poetry then was not the tour de force it became later. It was her singing in that infectious style of hers that endeared her to people.

And what was she singing about? I first heard two of those songs in the Mannings Hill schoolroom one rainy Saturday night in 1949. One proclaimed the virtues of courtesy:

Treat everybody good and square

Gi’ horse him grass, gi’ puss him pear

Mine yuh manners, don’t forget

Howdy and tenky bruk no square

Cho: Howdy, howdy do

Tenky, thank you’

Beg yuh pardon, excuse me

Practise up yuh courtesy

The other encouraged people who could not afford beef, to “cook a chicken” which they could easily raise in their yards.

Cook a chicken

Cook a chicken

Take my advice there is nothing nicer

Cook a chicken

But Miss Lou was finding it hard to make a living, and so she returned to England for a time and then went to New York where she and Eric Coverley directed a musical, “Day in Jamaica,” which opened at Saint Martin’s Little Theatre in Harlem and moved around church halls in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut.

They soon got married and returned home where she was appointed drama officer with the Jamaica Social Welfare Commission and ultimately its director from 1959 to 1963, one year after the change of government. From 1966 until 1982 she composed and delivered Miss Lou’s Views, topical four-minute radio monologues.

I had the honour of sharing the stage with Miss Lou in two pantomimes in 1957 and 1958.

You hear about prima donnas, and you know Miss Lou was the first lady of stage. But the prima donna thing was not for her; she never displayed those qualities. She was just Miss Lou.

And therein lay her great charm. When she died, I reflected briefly on Jamaica’s national heroes. If Garvey’s mission was Black pride and pan-Africanism, and Bustamante’s was to launch a labour movement, the mission of Norman Manley was to forge a national identity.

Post emancipation, Norman and Edna Manley were the hand that rocked the cradle of Jamaican culture. For they gathered around them artists, writers, sculptors, musicians, actors and singers – including Louise Bennett. And they stoked the flame of nationalism which she caught and spread far and wide with her songs, stories, poems and performances.

Miss Lou credits her mother for handing the culture down to her, and preparing her for her life’s work. Beyond that, however, was her own spirit – buoyant, resilient and creative. I believe people will one day realise that her impact on Jamaica has been as great as that of any of our National Heroes. The day after I had that thought, I found an obituary by Antiguan Professor Gus John of the University of London. Here are excerpts:

“Her death marks the passing of a legend. Never mind historical icons such as Alexander Bustamante and Norman Manley; Louise Bennett was the mother, father, and soul restorer of the Jamaican nation.

“No one had done more to assist the Jamaican people in understanding themselves and their uniqueness as a people crafted from the ravages of slavery and colonialism than Miss Lou. The Honourable Marcus Mosiah Garvey focused upon the African identity of Jamaican and other African heritage people in the Diaspora and the need for us to reconnect with Africa and reclaim our heritage in the Motherland.

“Miss Lou devoted a lifetime to helping the nation to understand who it is, where it came from, how where it came from shaped who it is, and how, in the process, ways of communicating were forged which were unique to Jamaica and the way the nation experienced and related to its world and to the world outside itself.

“She brought the art of dramatic expression to her exploration, interpretation and use of the Jamaican language, validating it as a language long before it was accredited as such in the 1960s, largely through the work of people like Frederic Cassidy and Robert Le Page.

“The bibliography in the seminal writings of both these academics, especially Jamaica Talk (Cassidy: 1961) and Dictionary of Jamaican English (Cassidy & Le Page: 1967) include references to Louise Bennett’s work dating back to 1942 when the Gleaner published her Dialect Verses.

“She did more than most to develop an awareness and understanding of Jamaican folklore, of the sayings, proverbs and philosophies, the values and principles of the ordinary working people. Using the medium of poetry, drama and storytelling in what was predominantly an oral tradition, Miss Lou put the Jamaican people in touch with themselves, with their wisdom, their irony and their quirkiness.

“Above all, she put them in touch with their inner selves and their connectedness to Africa by pointing up the fact that the entire society, and its culture, is riddled with African retentions.”

To be sure, long before that, Miss Lou had attracted serious analysis and praise from Jamaican professors Rex Nettleford, who described her as “a performer, accomplished and unrivalled,” and Mervyn Morris, who took the trouble to study her and write the assessment, On Reading Louise Bennett Seriously at a time when many in the society were still turning up their noses at her efforts.

In 2003, at age 83, after living in Canada for several years, Miss Lou was invited to pay an official visit to Jamaica as the guest of the PJ Patterson Government. The welcome she received was lavish, emotional, genuine and universal. Jamaicans found they were reaching out to a part of themselves they suddenly discovered they had lost and had been yearning for. She was deeply touched by her reception and spoke about it with great joy on her return to Canada.

Two years earlier my wife Merle and I spent a long day with her because I was interviewing her for the video called Visiting with Miss Lou. It was a very instructive occasion. We learnt much more about our mores, our expressions, our history, our culture. And it is culture – not race, not colour, but culture – that is the essential element of a people.

And what is Jamaican culture? One definition of culture says culture should be regarded as the set of distinctive spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features of society, and that it encompasses, in addition to art and literature, ways of living together, traditions and beliefs.

So, culture in the Jamaican sense, in Miss Lou’s sense, is: cotta, grand market, boogooyaaga, yabba, grater-cake, labrish, mango-time, rolling calf, jonkunoo, August Mawnin, pantomime, fenkeh-fenkeh, dinki-mini, jerk pork, blue draws, dookunno, dance-hall, patties, dat, asham, mento, gizzaada, church, kin-teet, kin poopalick, blue draws, do-good man, pasero, my points, key-spar, pocomania, copasetic, six-love, nine-night, duppy, ska, cut-eye, clear off, boonoonoonoos, walk off, pocomania, everything is everything, kiss me neck, level vibes, ’ug up dat, yow! and gweh!

Miss Lou transcended all barriers. She was happiest among children, and her Ring Ding show on the JBC, which was scheduled to last seven months and ended up lasting 12 years, is eloquent tribute to that.

In the process, she created her alter ego, Auntie Roachie, who spoke her deepest thoughts for her. But she was at ease among all age groups, all races, because she was always herself – the cheerful raconteur of stories, depicting the culture of Jamaica; depicting the Jamaican.

As Gleaner columnist Melville Cooke wrote on August 3, 2006,

“When Miss Lou went to be with her very wise Auntie Roachie, I do not know how many people realised how revolutionary a person she was – cherubic smile, headwrap, bandana material and all. In a society where the unruly tongues of the Black majority have been subjected to as much straightening and controlling attempts as their equally unruly hair (with far less success), Miss Lou gave us the licence to ‘chat we chat.’ The process of legitimising language is a long and tenuous one, which requires not only that it is spoken in informal, but also in formal settings.

Evening Time, Miss Lou; Evening Time…

Ress yuhself at ease.

© Ewart Walters. Excerpted from “We COME FROM JAMAICA: THE NATIONAL MOVEMENT” 1937-1962” Reproduced with permission of the author

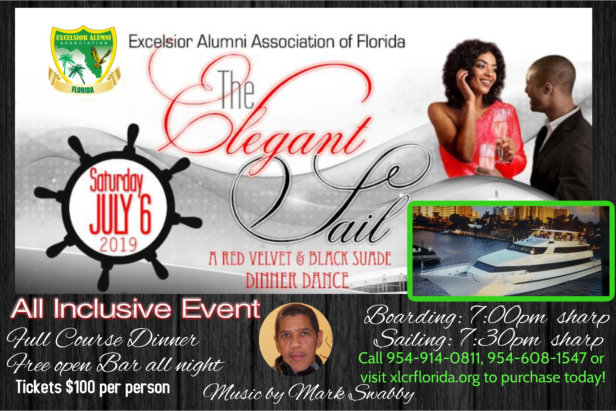

Xmax Bash 2019

Xmax Bash 2019 The Eagle Eye 2019

The Eagle Eye 2019 Founder's Day 2016

Founder's Day 2016 Kiwanis Xmas in July

Kiwanis Xmas in July Xmas Bash 2016

Xmas Bash 2016 Blakka Comedy 2016

Blakka Comedy 2016 EXED Founder's Day 2017

EXED Founder's Day 2017 2017 Xmas Bash

2017 Xmas Bash Family4Life Homeless Shelter

Family4Life Homeless Shelter